“If you tell people something and show them a photo, then they are more likely to believe what you are saying – even if what you say isn’t true.”

My biggest knitting pattern peeve is photography that is a deliberate misrepresentation of the article in question.

There are a lot of tricks to accomplish this kind of misrepresentation. And it is totally unfair to the knitter, who picks a project based on the pretty picture, and then finds herself with a finished garment that isn’t what she thought it would be — or worse, an unfinished garment!

I tend to think of magazines as being the big offenders here, because they have tighter deadlines, and I suspect when you work at a magazine there’s a certain amount of “oh, well — there’s always the next issue”. But I see more and more books out there with deceptive photos, too.

What happens on a photo shoot? From a Cosmopolitan article:

The lie: These clothes fit perfectly.

The truth: …Safety pins are used to make minor adjustments to the fit of sleeves and pants, making them look narrower than they really are, but when a garment is particularly large or a model particularly small, clamps are needed to hold back all the excess fabric. The waists of skirts and dresses are almost always clamped to give the illusion that the clothes (and the models) have more of a shape than they actually do… Sometimes there are so many clamps down a model’s back that from the side she starts to look less like a human and more like a stegosaurus.

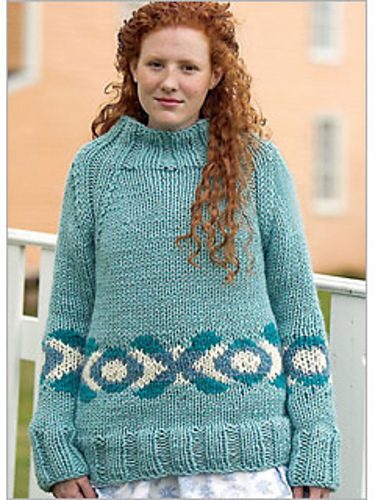

One memorable example of this trick was published in a KnitScene magazine over 10 years ago. They had a bulky knit raglan pullover on a young, slim model, and the fit of the raglan lines was just so wrong that I had to look at the instructions to see what was up. Turned out the pattern was given in exactly two finished sizes: 35″ or 53”. Obviously the model garment had been knit in the 53″ size, and they must have had to wad up about half of it behind the model’s back for the photo shoot.

One memorable example of this trick was published in a KnitScene magazine over 10 years ago. They had a bulky knit raglan pullover on a young, slim model, and the fit of the raglan lines was just so wrong that I had to look at the instructions to see what was up. Turned out the pattern was given in exactly two finished sizes: 35″ or 53”. Obviously the model garment had been knit in the 53″ size, and they must have had to wad up about half of it behind the model’s back for the photo shoot.

Another clue here is the way the model’s arms are in such an unnatural position, being held straight down at her sides. It may not look too odd at a glance, but try it yourself for a couple of minutes and you’ll see it isn’t something you normally do. This is a picture of a woman with something to hide!

So, what knitters need are preventive strategies to match the photographer’s tricks.

Trick #1: Faking the Shaping

One of the most common photography tricks in knitting is when they take a sweater that has no side shaping whatsoever — usually billed as “easy to knit” somewhere in the description (which it is) — and make it look as if it is shaped, because shaped sweaters generally look nicer. This is easily accomplished with the clipping trick mentioned above. Voilà! Curves!

Solution: Check the Schematic

Sometimes you can get a clue just from the picture. The sweater may simply look like the fabric is being pulled to the back. The sweater may not fit properly: the shoulders may not sit right on the model. A sure giveaway is if the band on a cardigan looks like it is being pulled open. Another clue is if the rows look distorted: in other words, they are not hanging straight but instead look as if as if they are being pulled to the back.

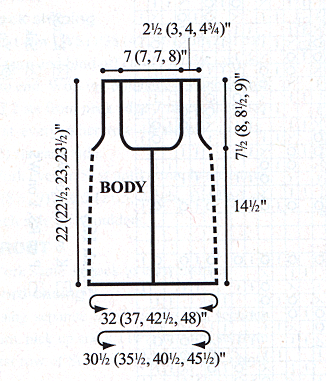

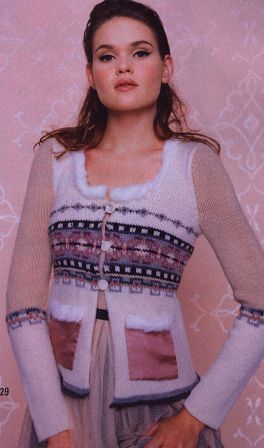

My personal experience with this problem was with the “Nutcracker” sweater, which looked like this cute little fitted cardigan in the magazine. But it had a schematic that looked like this:

The most reliable way to tell what shape a sweater really is, is to check the schematic. If it has straight sides, as below on the left, then it is boxy and doesn’t have any shaping. It has to look like the one below on the right for it to be a shaped sweater. If the photograph looks shaped, but the schematic is not, be aware that what you will end up with won’t look like the photo. I didn’t!

In fact, I later figured out that I could mathematically prove what they had done. See the bottom of the Fair Isle panel, where there are 8 square grey motifs across the waistline? Those are 8 stitches apiece, for 64 stitches across the front, and presumably a total of 128 stitches front and back. But at that point in the pattern, there are 168 stitches on the needles! 40 extra stitches. The math can’t lie. In that photo, there are 8 inches of extra fabric wadded up behind her back.

The one exception I can think of to this rule is a sweater with negative ease, i.e. where the knitting is expected to stretch to fit and hug the body. As an example, my Sassy sweater is just a tube of ribbing with no side shaping. The tube is smaller than my body, though, so when I put it on, it conforms nicely to my curves.

If you are considering a pattern with no schematic, I strongly urge you to pass, and instead look for a similar pattern that does have one. Schematics are useful in knitting, fitting, and finishing, and are a sign of thoughtful design. Lack of a schematic is a big red flag, especially given modern publishing technology. There are too many knitting patterns available out there to take a chance on knitting a mystery garment that may disappoint.

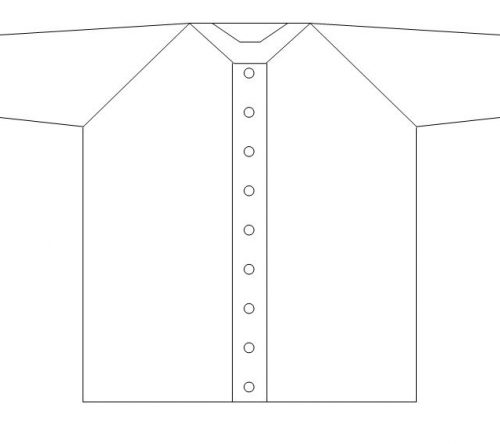

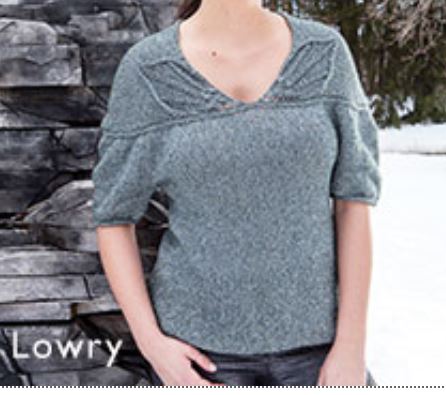

Trick #2: Hiding the Armholes

Beware any pattern that does not have a picture showing a clear view of the armholes with the model holding her arms in a natural-looking position. It could be that the sample garment is simply too big for the model, or it could be that there is something else to hide about that armhole, like in this pattern.

The only real clue here is that the arms are being held in the now-familiar guilty position.

But what is really sneaky is that they include this close-up of the underarm, which looks pretty OK, unless you notice that the grey armhole — coincidentally photographed against grey rocks — actually goes all the way down to just under the bustline:

Basically, the design is a modifed batwing-sleeve, which in itself is not bad — but maybe they think so, because they sure don’t mention anything about it in the description, and you can’t easily tell it from these two photos.

In fact, I would not have noticed it, except for the fact that when it first came out in the company’s weekly newsletter, they used this third photo, which clearly showed the batwing sleeve you were going to get, and which has subsequently disappeared from everywhere. Hmmmm.

Solution: Be Suspicious of Weird Arm Positions

The armhole is the hardest place to get a sweater to fit properly, so if you are only being shown an armhole with the arms held directly against the body — or sometimes held overhead, so as to stretch out any extra fabric — or any other pose that looks a little strange — be suspicious. Also look for things like hair or a scarf covering the armhole completely.

Again, it may just be that the model garment is a poor fit for the actual model, like the two-sizes-fit-all raglan in the first example — but it could be something else, and you want to be fairly certain you know what it is before you cast on, if you don’t want to be surprised. So, check the schematic if you have access to it, and look on Ravelry for pictures and reviews of other people’s projects, to see what else you can find out.

Another example of a design issue that is being hidden by a similar photography trick, and that is also very hard to spot, is detailed in this post.

Trick #3: Hiding Anything Else

There are some photography tricks that are truly hard to beat. Several years ago I heard a designer relate this story of a design she had submitted to a magazine:

She designed a fairly plain pullover with a large, face-framing, stand-away collar as the focal point. The magazine paid her for the design, and when the issue came out, she flipped through it looking for her sweater. She didn’t recognize it the first time through. She had to go back through the magazine again, page by page, to find it.

First of all, they had embellished the front of the sweater with a big ol’ snowflake made of white buttons. I repeat verbatim what she said: “I’m not dissin’ the snowflake, but it wasn’t my design.”

OK. You could always decide to leave that off. But the unforgivable part was that they photographed it on a woman who was supposed to be baking cookies or something, flanked by two smiling children, and she was looking down at what she was doing, and her hair hung down over her shoulders and entirely covered the large collar. I saw the picture myself. You couldn’t see the collar at all.

The designer said she always felt sorry for the poor knitters who went to make what they probably thought was a basic crewneck sweater, and then out of nowhere this huge collar pops up. Even worse, I doubt that the collar would even show up on the schematic, if it were something that was to be picked up and worked later.

Another memorable episode was when one of my students came to class with a question about a baby sweater she was knitting. She had bought a book written by a well-known British designer of children’s knits, and was making a wraparound-style sweater for a 6 month old baby.

The directions had her start by knitting a long, 2″ wide strip — and she was mystified as to what part of the sweater she was doing. The front band, perhaps? I read through the pattern — there was no schematic — and finally, I told her she was knitting the tie.

“What tie?” she asked.

“Well, there are ties that go from either side to tie in a bow in the back,” I told her.

She was horrified. “But this is for a baby who can’t even sit up yet!” she exclaimed.

We all looked at the 2 available pictures in the book. Both of them showed an adorable little blond toddler girl, in a cute pink wraparound sweater, photographed directly from the front, with her arms firmly down at her sides. Absolutely no evidence of the ties.

One could suspect they might have been deliberately hiding the ties. The one 2″ wide tie that my student had already knitted certainly suggested that the bow in the back was going to be enormously bulky and unattractive.

I suggested that she could change the knitted ties to ribbons, or replace them with buttons — either of which would, in effect, give her the sweater she THOUGHT she was knitting. (And why they didn’t do that in the book, I’ll never know. Although one extremely cynical possibility is that the addition of the knitted ties means they get to sell you another ball or two of yarn.)

But I could tell from her face that no matter what we did to pick up the pieces, the project was now ruined for her. Here she had trusted the name on the book, spent the money, bought the specified, pricey, designer yarn — and spent a lot of time knitting that stupid tie, to boot. Now she felt betrayed, as if she had been lied to. Well, in my opinion, she had been lied to.

Which is the part I find unforgivable. Designers, book and magazine publishers, yarn companies — it seems like they all do it on some level — yet they aren’t the ones who live with the consequences. When I was actively teaching, I was the one who ended up explaining the lies, trying my best to pick up the pieces, consoling a knitter whose time and money had been wasted, and whose pleasure in her craft had been sabotaged.

Solution: Read Through the Pattern

Yes, I know, this doesn’t sound very fun. And you can’t read through a pattern that you haven’t purchased yet. But it’s the only way I know of to avoid unpleasant surprises like the two I just mentioned.

You don’t need to do this with every single pattern you see or save or download, nor do you need to do it for something like a relatively low-commitment simple cowl. But I do definitely recommend you do this with anything major that you are seriously considering casting on. At the very least, before you buy the yarn or make a gauge swatch, skim through the various sections and pieces of the garment, and read the “Finishing” section a little more thoroughly. If you see a whole paragraph under “Collar” then it’s a safe bet there is more to it than a simple ribbed band.

And look at it this way: spending a few minutes skimming a pattern, only to find out it has something you really don’t like, saves you a whole lot of knitting time, not to mention frogging time, and even yarn money! It’s well worth a few minutes to make sure you’re getting what you think you’re getting, or that you know what modifications you’re going to make, than to waste time and money on a disappointment.

2 comments for “Project Prep: Beware of Photographs – More Examples”